A humane backyard is a natural habitat offering wildlife plenty of food, water and cover, plus a safe place to live free from pesticides, chemicals, free-roaming pets, inhumane practices and other threats. And it's so easy to build!

Focus your ideas

The good news—and the bad news—is that there are endless ways to make a difference. Ask yourself: What can you realistically manage? What’s achievable in your community? Which concepts are easiest to explain to newbies?

Maybe you’ll work within your HOA to implement eco-friendly landscaping practices, persuade your district to swap outdoor lights for motion sensor lights that prevent insect deaths, recruit 50 neighbors to take the Humane Backyard pledge, or join forces with your municipal animal control agency and ask them to join the Wild Neighbors program and pledge to use humane solutions to wildlife conflicts.

Cape Conservation Corps hosts weekly invasive plant removal events throughout summer, kicking off the season with wine, pizza and an information session on a neighbor’s driveway, as well as an annual native plant festival with local plant sellers and environmental nonprofit representatives. In 2020, almost $9,000 worth of plants sold out in 55 minutes.

Smucker started Stream-Link Education after learning that “planting trees is the cheapest thing you can do for water quality for the Chesapeake Bay. Planting trees next to streams hits the home run.” Fifteen years later, the nonprofit has engaged 3,000 volunteers and planted 26,000 trees near streams.

Consider linking your community goals to larger efforts to narrow your focus and lend you legitimacy. Green Team Urbana’s goals mirror those of Homegrown National Park, a nationwide grassroots effort to restore biodiversity with a collective 20 million acres of native plants, and Cape Conservation Corps borrows ideas from Weed Warriors, which trains people to remove nonnative, invasive plants from public land.

Create a team Facebook group or page to help people find and join your cause.

What can you realistically manage? What’s achievable in your community? Which concepts are easiest to explain to newbies?

Gather info and support

Once you have a plan, introduce yourselves to related people or groups: your HOA or town manager, gardening clubs, local Master Gardeners and Master Naturalists, community-supported organic farms, Scout groups, service organizations, plant nurseries, state sustainability and forestry services, newspaper editors, science teachers, eco-action clubs, grassroots groups and nonprofits.

Smucker originally just knocked on doors and asked, “Hey, would you like some trees along your stream?” He planted those trees with social services organizations before founding Stream-Link and partnering with other small nonprofits and local government agencies.

Don’t be discouraged if some people initially seem skeptical. Green Team Urbana planted seeds that grew (no pun intended) in unexpected places: There was the busy library board member who, unprompted, included Green Team Urbana-themed gift baskets in local schools’ fundraising raffles, and the quiet HOA committee member who revealed he was a retired National Park Service exhibit designer and offered to create our educational pollinator garden sign.

Make it accessible

Celebrate your community’s progress, says Wildberger. Four times a year, the Corps designates a “Habitat Hero” who’s incorporating native plants in their yard to receive a hand-painted yard sign, a small feature in local newspaper The Caper and a spot on the group’s annual garden tour.

Recognizing people’s efforts—like the 2019 Habitat Hero they call “Sea-Oats Ginny,” known for handing out native sea oats seedlings—fosters goodwill. When Wildberger stopped by Ginny Klocko’s house to ask if she’d be a Habitat Hero, “you would’ve thought I knocked on her door and handed her a million dollars,” she says.

In May, the Corps offered residents three free native shrubs for every invasive heavenly bamboo (Nandina domestica) plant they removed from their yards. Although the native shrubs were quickly claimed—resulting in the removal of around 100 nandina plants, known to be toxic to birds—one man who missed out asked Wildberger for help choosing and ordering replacement shrubs anyway. He ended up ordering $400 worth of shrubs and donating $100 to the Corps.

“It’s just a constant little drip” of awareness and opportunities to do better, says Wildberger.

Plant seeds in common ground

Even neighbors who seem indifferent to your cause might respond to a different angle: Not everyone feels fired up when they hear about herbicides and pesticides poisoning wildlife, but lots of people want to protect kids and pets from potentially harmful chemicals.

Similarly, plenty of people prefer nonnative plants, but they’ll likely also have a bird feeder. Tell them chicks desperately need the insects that native plants support and that the berries on their heavenly bamboo shrub can kill birds, and suddenly they’re outside with a shovel.

Our HOA wasn’t too concerned about erosion on steep, grassy slopes in our neighborhood, which can clog waterways and kill aquatic life. But when our landscaping contractor noted that mowing those slopes was dangerous and difficult, suddenly reforesting them with native trees—helpfully provided by local nonprofit Stream-Link Education and planted by volunteers—seemed like it could prevent a costly lawsuit.

You might also face more proactive pushback, such as this comment posted in my community’s Facebook group after volunteers planted hundreds of native trees on slopes: “Negative Nelly here—thanks for ruining our sledding hill once again—couldn’t have left a path at least? Same thing will happen as usual—the kids will knock them all down like last time. Sorry to be the hater!”

In the face of uninformed criticism, gently reiterate the purpose and thought process behind your project—in our case, the slopes were eroding at a shocking pace—and then ask the haters to help. “Thank you for sharing your concerns!” you might say or write, gritting your teeth into a smile and mashing hard on the exclamation point key. “Please help us out and ask your kids and neighbors not to knock down trees!”

Recognize and respond to genuine questions and constructive feedback—for example, one neighbor was concerned about walking past our pollinator garden with a family member who’s allergic to bees, and she was relieved to hear that bees are generally docile and that the garden would leave enough room for walkers to pass at a reasonable distance—but treat unhelpful criticism like a toddler’s tantrum, acknowledging people’s feelings and then distracting them with something to do.

It doesn’t matter why people join your cause—what matters is that they join.

Learn More About Humane Backyard

Want more content like this?

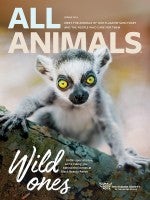

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe