Editor’s note: In late December of 2020, Congress approved a stimulus deal that extended the federal evictions moratorium until Jan. 31 and provided $25 billion in rental assistance. On Jan. 20, the new director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention extended the moratorium until at least March 31.

Things were looking good for Earlene* in Atlanta at the start of 2020. She had a job at Macy’s. She was renting a house with enough space for her teenage son and daughter and their three dogs, while saving to buy a place of their own. Then, in March, COVID-19 struck. Earlene lost her job. Her landlord told her she had to buy their rental or move out in 60 days because he couldn’t afford the property taxes. Soon she was putting stuff in storage and wondering what to do about her dogs: a Yorkie named Sage, a Lab-pit bull mix named Pearlie and a boxer named Falcon. It’s tough to find housing for dogs, especially big ones. She considered sleeping in her car.

“Hard times, that’s putting it lightly,” Earlene says. “People are gouging you. They know you’re desperate.”

A nonprofit called Paws Between Homes came to the rescue, arranging for Sage and Pearlie to go to fosters and Falcon, more rambunctious, to go to a kennel for 90 days. While Earlene and her children stayed with relatives, then at a hotel, Cole Thaler—a housing attorney who founded Paws Between Homes—brought Pearlie and Sage for visits and searched for dog-friendly rentals.

Finally, Earlene found a four-bedroom outside Atlanta. Paws Between Homes paid the $400 pet deposit. In October, her family—including the dogs—moved in.

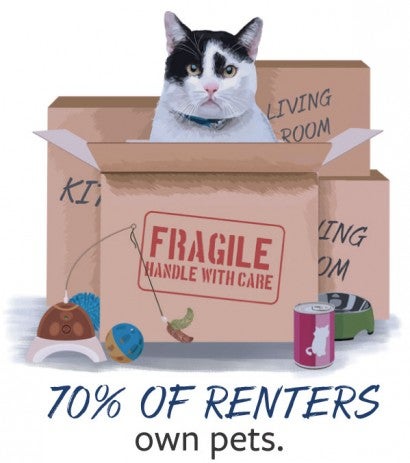

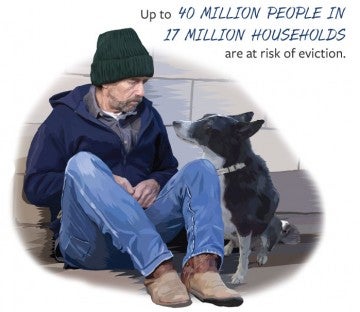

During the coming months, millions of people with pets will face circumstances similar to Earlene’s as federal, state and local pandemic eviction moratoriums expire and unemployment and rental assistance are exhausted. A tsunami of evictions is expected to hit in January after a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention moratorium expires Dec. 31 and back rent and late fees come due. The Humane Society of the United States’ Pets for Life program is working with local animal welfare groups to keep people and their pets together as the pre-COVID affordable housing crisis swells.

“We are in a unique position,” says Amanda Arrington, senior director of Pets for Life, which provides support services to pet owners in 50 underserved communities across the country, directly and through local partners. “If we want to keep pets in their homes, we have to keep people in their homes.”

If we want to keep pets in their homes, we have to keep people in their homes.

Amanda Arrington, Senior Director of Pets for Life

Late last summer, the HSUS started hosting webinars on the eviction crisis for the animal welfare community and published an online toolkit that describes how to provide the support pet owners facing eviction need, how to raise public awareness of the problem and how to push local, state and national governments—and the housing industry—to respond to the crisis. As people have started to lose their homes, Pets for Life and our allies are using the strategies outlined in the toolkit: connecting tenants with legal help, temporary places to stay and housing that accepts pets, arranging short-term foster care, paying pet fees so renters can afford leases and providing supplies and veterinary care.

In Atlanta, Pets for Life, operated by LifeLine Animal Project, is sending referrals to Paws Between Homes, providing temporary housing and supplying community support like food, leashes, cat litter and veterinary care. In Baton Rouge, a Pets for Life partner called Companion Animal Alliance is reaching pet owners in need at food banks: When a woman lost her restaurant job because of the pandemic and was evicted, the Alliance supplied everything required for her two dogs, five cats, two ducks, two chickens and parakeet until she found a new job and a new home.

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe