It started in 2002: The bears around Durango, Colorado, came down from the hills to feast on the city’s garbage. Normally, natural food—nuts and berries and acorns—keeps them in the woods, but a series of droughts and late freezes in 2002, 2007, 2012 and 2017 left them hungry. Despite their fear of people, they showed up in subdivisions and more and more in the city’s downtown. They scattered backyard beehives and raided bird feeders, shimmying up poles to sip nectar set out for hummingbirds. They climbed into orchard trees for fruit and hauled themselves onto decks to look inside houses, which they sometimes entered, leaving kitchen floors strewn with food yanked from the fridge. They splintered fences and busted into garages and surprised residents grilling steaks. They ambled down crowded sidewalks and in at least one instance temporarily closed an elementary school. They stood full height to reach into commercial-sized trash bins. And, again and again, they knocked over trash containers in driveways and alleys to get at garbage.

Bryan Peterson, a Midwestern transplant to the city who founded Bear Smart Durango in 2003, drove around at night when the bears were most active, taking photos of garbage piles and plotting locations to alert officials about the number of bears who were in town. Independently, Colorado Parks and Wildlife had chosen Durango for a study. With all the human-supplied food, residents assumed the bear population was growing and that’s why they were seeing so many bears—there must be more of them.

To protect both bears and people as black bear populations recover and human populations grow, the Humane Society of the United States, advocates such as Peterson, researchers such as Johnson (now a research wildlife biologist with the United States Geological Survey), and wildlife and government officials are working to change human behavior. Their efforts are particularly urgent in the West. There, climate change, more frequent droughts, wildfires and bears spending longer periods outside their dens—Johnson found that in Durango during warmer years or when they are feeding on human food they emerge earlier and return later—are increasing interactions between bears and people.

When encounters and conflicts increase, so often do calls for bear trophy hunts, which currently take place in 33 states, including Colorado. During the last two decades, the number of black bears killed in the United States has risen from 34,000 to 51,000, according to a report the HSUS will soon release. The HSUS works to limit and end bear hunts, arguing that hunting has not been shown to reduce human-bear conflicts and may even increase them when bait is used to lure bears. Last year, the HSUS petitioned the California Fish and Game Commission to halt the state’s hunt until it better understood the bear population and the impact of drought and wildfires. This year, the HSUS helped defeat an attempt to reopen a spring bear hunt in Washington state.

They’re driven almost solely by food. That’s why being bear aware is so critical. Bears have an amazing sense of smell—seven times better than a bloodhound. All it takes is one person not knowing what they’re doing, and the bears will come.

Samantha Hagio, the HSUS

Instead of killing bears, the HSUS and others are promoting nonlethal means of reducing conflicts. A series of seven HSUS webinars created last year for different regions features bear experts describing what’s proved effective in Durango and elsewhere: removing human food sources that attract bears (see tips below). If that’s done, when natural food shortages cause bears to look for human food, they won’t find it and will move on.

“They’re driven almost solely by food. That’s why being bear aware is so critical,” says Samantha Hagio, HSUS director of wildlife protection. “Bears have an amazing sense of smell—seven times better than a bloodhound. All it takes is one person not knowing what they’re doing, and the bears will come.”

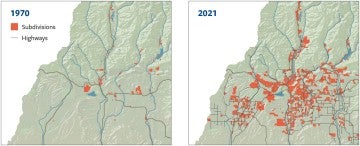

There are few places in the country where humans have tried harder to coexist with bears than Durango. Other Colorado communities—including Colorado Springs, Boulder, Steamboat Springs and Vail—are using what researchers learned there. During the past 50 years, development around Durango has brought people and bears together as humans move farther and farther into the hills, in subdivisions built for retirees, second homeowners and tourists drawn by the beauty of the mountains and the Animas River Valley. The radio collars researchers put on individual bears show their movements: During a bad food year, one traveled 15 to 20 miles from high in the La Plata Mountains down into the Animas River Valley where people live. Most live closer to town and turn to human foods when natural ones are scarce.

“They know exactly where to go for food,” says Johnson. “They have these amazing memories. They know the landscape.”

In 2008, following the examples of Snowmass Village and other Roaring Fork Valley communities in Colorado, La Plata County, which surrounds Durango, passed an ordinance requiring residents to secure their garbage from bears. The city of Durango followed in 2010, requiring residents to keep garbage in a locked bear-resistant container or in a garage or shed. But most residents did not comply. Only 10% had bear-resistant containers at that point.

So in 2013, Johnson and other researchers gave more than a thousand bear-resistant containers from Colorado Parks and Wildlife to residents of two neighborhoods. They found that when at least 60% of people on a city block secured their garbage from bears, latching the two clips on the containers, conflicts significantly dropped. To cover a majority of the city and increase the % of containers that were secured, in 2018 to 2019, the city supplied residents in other neighborhoods with automatically locking bear-resistant containers. Those worked even better. Researcher Cassandre Venumière-Lefebvre, a doctoral student at Colorado State University, found that more than 60% of bears’ attempts to get garbage inside containers in the city failed.

“Bears come in and they try the can and then leave because it doesn’t open,” says Venumière-Lefebvre, who rose early mornings to observe them. “They just try for a few seconds, and then move on. You see the bear walking down the alley and trying one, two, three.”

Right now, around 75% of Durango’s garbage containers are bear resistant. The city’s goal is to reach 100%.

It’s not enough for individuals to bear-proof their properties. Everyone in the community has to participate, say researchers and advocates.

“It matters what the people are doing on your block,” Johnson says. “It depends on your neighbors whether you are likely to have a conflict.”

Beyond the city, Peterson and Bear Smart Durango urge residents to secure their garbage, distribute electrified mats that deliver a small but persuasive shock to bears approaching doors, work with volunteers to gather fruit in orchards so that it does not attract bears and help put electric fences around hives.

In one of the mountains north of the city, Erin Jameson and her family live in a house up a steep winding road, with a beautiful view and bears passing by all the time. Before they moved there six years ago, the grandparents of the previous owners cooked salmon, put the skin in the garbage and stored that in the garage. Bears tore down the garage door.

Mindful of the danger, Jameson, who served as finance and operating director for a community foundation that funded Bear Smart Durango, keeps her garbage in locked tubs in the garage. She has no bird feeders. And she asked Peterson to surround her 11 beehives with a six-strand electrified fence so they wouldn’t draw bears.

“We’re in their territory,” she says. “I guess I feel it’s my responsibility to make it safe for them.”

We’re in their territory. I guess I feel it’s my responsibility to make it safe for them.

Erin Jameson, bear advocate

Peterson says he’s tired of just educating people. After years of visiting schools and summer camps and stores and fairs and homeowners associations, after showing hikers how to use bear spray and campers how to store food, after setting up trail cameras and inviting guest speakers and leading hikes and organizing events like the “Spring Bear Wake Up Social,” he says there are still too many residents who haven’t changed their behavior. This year, Colorado Parks and Wildlife is giving away $1 million in human-bear conflict reduction community grants. In July, Peterson’s group, Bear Smart Durango, was awarded $206,539. It will cover two years’ salary for a county enforcement officer who can cite and fine people for not securing their garbage. It will also pay for bear-resistant trash bins and food storage lockers.

Another $225,000 will fund a five-year project by Colorado Parks and Wildlife in the Eagle and Roaring Fork valleys to see if human-bear conflicts in this area can be managed through nonlethal means rather than increased hunting, says Mark Vieira, carnivore and fur bearer program manager for the agency. “It’s going to be up to the communities and the stakeholders.”

Late one afternoon in May, when bears have emerged from their dens to search for food, Peterson goes to check on a La Plata County garbage transfer station, which for years bears raided. Garbage used to be strewn all over the neighboring hillside. People in a subdivision on the top of the hill watched bears cut through their neighborhood on the way to unsecured trash bins.

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe

Garbage and recyclables: Store in locked bear-resistant trash containers or in a locked garage or shed. Freeze meat or fish scraps until the day of garbage pickup.

Garbage and recyclables: Store in locked bear-resistant trash containers or in a locked garage or shed. Freeze meat or fish scraps until the day of garbage pickup. Compost: Keep in bear-resistant containers or surround with electric fencing.

Compost: Keep in bear-resistant containers or surround with electric fencing. Chicken coops and beehives: Protect with electric fencing.

Chicken coops and beehives: Protect with electric fencing. Pets: Feed pets indoors and store their food inside.

Pets: Feed pets indoors and store their food inside. Grills: Clean thoroughly after each use.

Grills: Clean thoroughly after each use. Fruit trees: Harvest ripe fruit promptly.

Fruit trees: Harvest ripe fruit promptly. Bird feeders: Feed birds only in winter when natural food is scarce (and bears hibernate).

Bird feeders: Feed birds only in winter when natural food is scarce (and bears hibernate). Houses and garages: Keep doors and windows shut and locked—or locked in place with an opening too small for bears. Do not vent cooking odors outdoors.

Houses and garages: Keep doors and windows shut and locked—or locked in place with an opening too small for bears. Do not vent cooking odors outdoors. Visiting bears: Chase off black bears by shouting or throwing sticks, stones or tennis balls.

Visiting bears: Chase off black bears by shouting or throwing sticks, stones or tennis balls. Camping: Store food in bear-resistant containers or hang out of reach. Dispose of garbage in bear-resistant trash cans. Clean grills and tables.

Camping: Store food in bear-resistant containers or hang out of reach. Dispose of garbage in bear-resistant trash cans. Clean grills and tables. Hiking: Bring bear spray, hike with a buddy and make noise as you go. Leash dogs or, better yet, leave them home.

Hiking: Bring bear spray, hike with a buddy and make noise as you go. Leash dogs or, better yet, leave them home.