When Rebecca Cary was in second grade, she started an animal club with her friends in the neighborhood. The group hosted a school bake sale to support manatees and visited an animal shelter with their parents. Although Cary doesn’t remember the details of the visit, she does remember thinking that she too wanted to help animals when she grew up.

I knew I wanted to work with animals, I just didn’t know how.

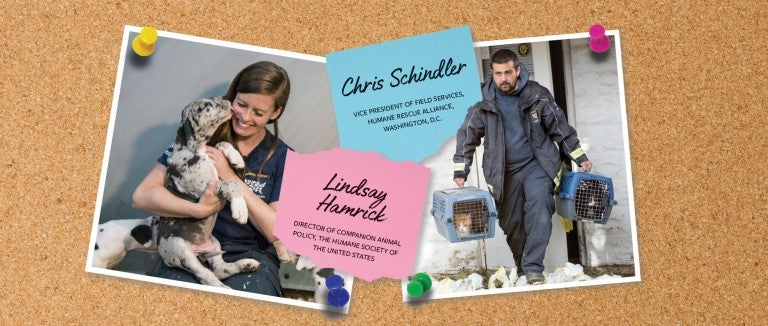

Lindsay Hamrick

Help the animal-loving kids in your life get out of the “You can be a veterinarian!” rut by exposing them to all sorts of animal welfare opportunities.

Check with nearby shelters and animal sanctuaries for volunteer openings. Although some organizations restrict minors’ interactions with animals, others welcome pint-size advocates. Look for organizations with humane education programs or kid-focused opportunities, such as reading to nervous shelter dogs.

Gather friends and make it a group effort! Last summer, an Atlanta-based Girl Scout group built a greenhouse at the HSUS-supported Project Chimps sanctuary. Not only did they earn an award for their service, but they also learned about the chimpanzees who live at the sanctuary.

Animal-loving teens can seek out colleges with programs related to animal welfare. Canisius College, Tufts University, Appalachian State University, New York University and the University of Colorado all have such programs, but that’s not an exhaustive list. And of course, you don’t need an animal degree to get started!

Any career becomes animal-centric when you’re working at the right place. Check out the (incomplete!) list below, and consider less-common organizations in your search: emergency response organizations, nonprofit veterinary clinics, dog boarding facilities, plant-based food companies, low-cost spay/neuter organizations, pet sitting services and more.

accountant

database manager

human resources manager

groundskeeper

volunteer manager

fundraiser

kennel manager

shelter veterinarian

wildlife rehabilitator

pet retention counselor

adoption coordinator

trainer/behaviorist

veterinary technician

advocacy journalist

videographer

social media manager

graphic designer

public relations specialist

web developer

conservation biologist

researcher or zoologist

plant-based food scientist

lawyer

animal protection lobbyist

animal cruelty investigator

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe