Flying back and forth over Cape Cod Bay, a survey plane spotted a half dozen of the world’s rarest creatures: North Atlantic right whales. Such sightings are good news. The species hovers near extinction—by one estimate, fewer than 360 remain. Each time researchers locate a whale, they take pictures and record the animal’s condition and position, so they can add that information to an online catalog.

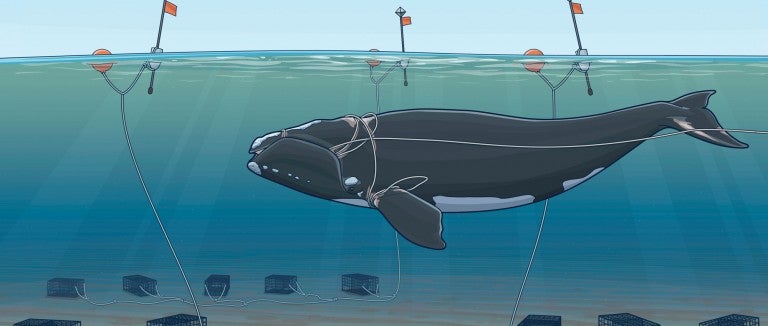

But the survey crew that day in April 2011 realized one of the whales was in trouble. A length of thick rope used to attach a buoy on the surface to lobster or crab traps on the ocean floor trailed from either side of her mouth. If it was not removed, it would lodge further into the baleen she used to strain tiny zooplankton from the sea. The heavy line’s drag would tire her as she swam and its polypropolene fibers would saw deeper and deeper into her skin, perhaps even her bone. Over time—starved, exhausted, wounded and in pain—she would die.

The aerial survey team radioed back to the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown. Fortunately, the Center’s Marine Animal Entanglement Response Team was on the water just a few miles away. Alerted by the plane, the team arrived where the whales were feeding around 3 p.m., while there was still good light. Lisa Sette steered their boat within 30 feet of the entangled 50-ton female—later identified as 4040 in the catalog, a 3-year-old given the name Chiminea because of the shape of the bumpy white growths on her head. From the bow, Brian Sharp used a grappling hook to attach a buoy and 60 feet of line to the whale. Immediately, Chiminea left the rest of the whales and started swimming to the northwest. Sette and Sharp took the end of the line and got in an inflatable dinghy. Water washed over the bow as they shot across the bay behind Chiminea. Sharp added a second buoy to the line to try to slow her down and keep her at the surface, but she dove, taking both floats briefly under. Finally, the rescuers pulled in close enough for Sharp to use a specially designed 30-foot pole and cutting tool to sever one side of the fishing rope in her mouth. Just as the sun was setting, after more than three hours, Chiminea surfaced to breathe, opening her mouth. The fishing rope dropped free and she swam vigorously toward the ocean.

Within 11 days, a plane crew sighted her off the outer beaches of Cape Cod. It was a victory, though Sette is careful not to overstate what they achieved: “You give the whale a chance.”

A decade later—10 years that were devastating for North Atlantic right whales—researchers spotted a mother and a calf in the warm waters off the Georgia shore where females give birth. It was Chiminea, now 13, with her firstborn: The 2011 disentanglement had saved more than one life.

This summer, teams like the one that freed Chiminea are standing by in New England and southeastern Canada in case they are needed to rescue North Atlantic right whales. But 90% of entanglements aren’t spotted and half of the attempts to free them fail. It will take more than rescues for the species to survive.

For decades, the Humane Society of the United States, the Humane Society Legislative Fund and coalition partners have used the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act to win federal protections for right whales, bringing a series of successful lawsuits to safeguard the species in its critical habitat. Now, with time running out, advocates are pushing for the biggest protection of all: the adoption of ropeless fishing technology that won’t entangle whales.

“We are killing them ... we need to change the gear,” says Sharon Young, HSUS senior strategist for marine issues, who for more than 30 years has tried to save North Atlantic right whales. Young has spotted the mist from their blow holes as a guide for whale watches, seen right whales feeding while she stood on a cliff over Cape Cod Bay and, once, watched a right whale breach just 15 feet from her boat, soaking her and rocking the research vessel. Today, Young submits comments on proposed federal rules and represents the HSUS on the advisory team to the National Marine Fisheries Service that recommends ways to reduce accidental killings of right whales. The next two decades will decide whether any North Atlantic right whales remain in a century, Young says. “It’s heartbreaking. I’m watching them wink out. Within 25 years, you’re looking at a species that’s swimming extinct.”

Under pressure from a lawsuit by the HSUS and its partners, the Fisheries Service is expected this summer to issue additional protections, such as requiring the industry to use rope that breaks more easily. But Young and other right whale advocates do not expect these to be enough. The whale population, which stood at 500 in 2008, has been falling drastically. There are only around 85 females of reproductive age. Deaths outpace births. Given the slow rate at which right whales reproduce, the species cannot withstand losing more than a single whale each year without risking extinction. Yet in 2020, there were two deaths detected, and in 2019 there were 10. Last July, the International Union for Conservation of Nature changed the whales’ status from “endangered” to “critically endangered.”

(Estimates based on available data.)

remain today.

remained at the population's peak in 2008.

are alive today.

bear the scars of entanglements.

Because of global warming, the zooplankton that North Atlantic right whales eat—Calanus copepods—have moved north. The whales have followed. They still stop in Cape Cod Bay in the spring to feed, but instead of migrating to the Gulf of Maine and the Bay of Fundy in the summer, many swim north to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Some disperse to areas such as the Great South Channel, off Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard, where zooplankton are more abundant, though less nutritious.

As they expend more energy for less food, right whales encounter greater hazards. They are crossing new, poorly regulated shipping lanes and traveling through a region off Maine and southeastern Canada with more and stronger long lines for lobster traps: Just like zooplankton, lobsters have shifted north, and to catch them more boats head into colder and deeper waters, dropping heavier gear at the edge of the continental shelf.

Female whales, who generally swim closer to the coast to protect their calves, are dying at a greater rate than males, especially from entanglements. (Fewer have been hit by ships recently because of seasonal restrictions on speeds and travel in U.S. waters that the HSUS helped win, and rules Canada rushed into place as whales started feeding farther north.) Those females who survive give birth at older ages and less often because they are in poorer physical condition. During the 2017-18 season, no calves were born at all.

“It’s alarming,” says Young. “Given the number of females, they should be having a lot more calves. But they can’t sustain a pregnancy.”

Whales who give birth often have their lives cut short. In February 2020, a plane spotted a female right whale 45 miles southeast of Nantucket. Her mouth was oddly ajar—a buoy was jammed in one side and the end of a line was sticking out the other. She could not feed normally or maintain her body temperature. The whale was 3180, also known as Dragon, a 19-year-old who had birthed three calves. Now she was thin and covered in orange parasites. Because she was far from shore and the waters rough, the odds of a successful disentanglement were tiny. No rescue was attempted.

Dragon will not be officially subtracted from the number of right whales unless six years pass without her being sighted, but given her poor condition she is presumed dead, says Amy Knowlton, a senior scientist at the New England Aquarium, which created the right whale catalog. “It’s just another sad story.”

Other whales are swimming injured despite disentanglement attempts. In October, Scott Landry, director of the Center for Coastal Studies’ Marine Animal Entanglement Response program, got a call about a male named Cottontail who was spotted south of Nantucket with rope coming out of his jaw. Landry and a team removed 200 feet of rope but stopped because they were running out of fuel. For a few weeks, they tracked Cottontail with a telemetry buoy while he was 150 miles offshore and the weather was bad. Then the buoy fell off. In February, a drone operator spotted the whale.

“He’s still alive, though just barely,” says Landry. “He’s losing all of his blubber, all his weight.”

Knowlton and Landry have written papers on how right whales suffered as wooden lobster traps were replaced with heavier wire ones and natural fiber rope with stronger synthetic “polysteel.” They count the scars: More than 83% of right whales show marks of entangling fishing gear. Young cites their findings as she argues for faster, stronger action by the Fisheries Service.

“These are mammals, they feel the same pain we do,” she says. “You see ropes sawing into a whale’s flesh, into their bone. That animal keeps swimming as long as it possibly can because that is what it has to do to live. But don’t think that animal doesn’t suffer.”

What’s needed, say experts, is the removal of hundreds of thousands of long lines—heavy ropes that connect buoys to lobster and crab traps on the bottom. The HSUS and its coalition partners already persuaded the Fisheries Service to require the industry to sink lines connecting traps so they rest on the ocean floor. But lines that run from the trap on the end of a sunken line to a buoy on the surface continue to snare whales like Chiminea.

Solutions exist: Short-term, the HSUS is pushing for temporary lobster fishery closures. Researchers have designed lines to break if an adult whale becomes entangled in them, with weak hollow-braided segments every 40 feet. Long-term, there is ropeless fishing gear that sits on the bottom until a vessel retrieves the traps, with no line connecting them to a buoy above. Researchers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution have developed systems that enable a remote signal to release a buoy and coil of rope from the ocean floor or inflate a balloon to lift the first trap in a line from the bottom up to the surface. Massachusetts lobstermen have successfully tested the technology. A federal omnibus bill that passed in December with HSUS and HSLF help provided $5 million for North Atlantic right whales, including money to cover the cost of new gear and develop ways the fishing industry can find gear without buoys floating on the surface. The SAVE (Scientific Assistance for Very Endangered) Right Whales Act would provide a further $5 million a year for 10 years.

Switching to a ropeless fishery will require overcoming strong political resistance, convincing the industry that the end of long lines does not mean the end of livelihoods. It will take five to 10 years, Knowlton estimates. Landry hopes disentanglements allow the species to survive until then.

“I want to get as many of these animals back into this population as we can while we figure out a way to deal with this,” he says. “Humans allowed these animals to become entangled. It’s humans who have to help the animals out.”

At press time, 16 calves, including Chiminea’s, had been born and survived in the 2020-21 season. This summer, if Chiminea and her calf escape being hit by ships or entangled in fishing lines, they will likely be feeding in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where Chiminea has been observed many times. Then in the fall, right whales will head south to the calving grounds, migrating down the East Coast, past buoys and lobster boats and cargo vessels, past sunbathers and swimmers on beaches, pursuing an ancient course.

We know right whales well now, each one. We can tell their life stories, trace their genealogies and even reconstruct the species’ history, using whaling ship logs and genetics. Science tells us that over the centuries North Atlantic right whales have adapted again and again to survive. But it also tells us there are limits. If the whales are to avoid extinction, it is we who must change.

Take action

![]() Draft a brief letter (300 words or fewer) to the editor of your local news outlet urging the National Marine Fisheries Service to protect right whales and push for ropeless fishing.

Draft a brief letter (300 words or fewer) to the editor of your local news outlet urging the National Marine Fisheries Service to protect right whales and push for ropeless fishing.

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe