In mid-October, when dolphin-costumed protesters and other demonstrators marched through pouring rain to the Japanese embassy in Washington, D.C., the men in suits out front gave only the slightest sign they noticed. “We’re going to show them that we’re not going away,” said Naomi Rose, senior scientist for Humane Society International, The HSUS’s global arm.

While passing garbage trucks were more emotive, showing their approval with thunderous honks, the message of the global Dolphin Day event was still a long way from reaching those who needed to hear it most: Japanese citizens back home.

Their government’s sanction of dolphin slaughter gained notoriety in other parts of the world following the release of Louie Psihoyos’ The Cove. But the defenders of the annual hunt in Taiji have made concerted efforts to keep their fellow citizens from seeing the film. The groundbreaking documentary exposes the practice of driving hundreds of dolphins ashore so a small number can be netted for sale to entertainment parks and the rest butchered for food. The dolphin meat, the film reveals, is contaminated with high levels of mercury.

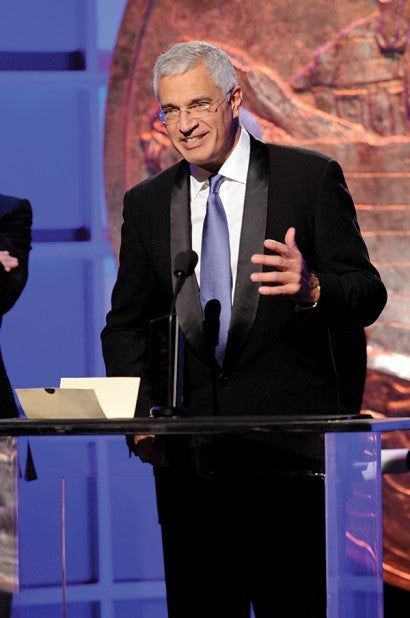

The Cove won a 2010 Oscar and a slew of other accolades. But it was the HSUS Genesis Award—which recognizes outstanding media portrayals of animal protection issues—that Psihoyos found to be the “most meaningful, heartfelt” honor, he says. The Cove was an easy choice for the award, says Beverly Kaskey, senior director of the HSUS Hollywood office. “It took documentary storytelling to a whole new level; it catapulted this issue onto the world stage.”

In this edited interview with senior writer Karen E. Lange, Psihoyos says he hopes DVD and electronic distribution in Japan, which was slated to begin in February, can finally turn the tide in Taiji.

In the film, there’s the idea expressed that if the killing of the dolphins can be documented and shown to the world, it will stop. But still the killing is going on. Why?

Because not enough Japanese people have seen the movie. Maybe a few tens of thousands of people, but we need millions. My feeling is once the film goes to DVD and electronic, that will create this tipping point. The killing of these animals is poisoning people. The animals that we had tested had higher levels [of mercury] than the ones that caused Minamata disease [a neurological syndrome caused by severe mercury poisoning] back in the 1950s and ’60s.

Some people have criticized the film by saying it’s anti-Japanese.

Dolphin shows really got started in America. That’s just as lousy a rap for the Americans as it is for the Japanese. [But] we aren’t slaughtering dolphins; we aren’t feeding the toxic meat to schoolchildren. If we were, there’d be this incredible outcry. The difference, I think, [is] the Japanese don’t even know about this. A large percentage of the dolphin meat is sold as “whale meat.” The Japanese are not getting the right story. This movie is really a love letter to the Japanese people because we’re giving them the information that their own government won’t give. If you go to the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, they actually have recommendations for a pregnant woman to eat bottlenose dolphin.

The Japanese theaters it’s been seen in are small art theaters?

Correct. When we first were coming out there, there were these ultra-radical groups. They’re sort of like neo-Nazis; they’re really more aligned with the Japanese mafia than anything. They were getting paid to just show up in front of the theaters and the distributor’s home. And they actually broke into the theater owner’s home and were shouting at the family with megaphones. They chased him out the back door. We paid for bodyguards to protect [featured activist] Ric O’Barry when he went there. We had injunctions made [against] these groups so they couldn’t show up in front of the theaters. They actually were successful in closing down three theaters that were showing the film. This created a marketing campaign for the film that was priceless to us. So now we have more awareness about our movie than probably Avatar.

One of the scientists in the film is suing you, wanting to be removed from the film.

Dr. [Tetsuya] Endo. He claims he didn’t know we were doing a film about dolphin hunting. But Dr. Endo is world famous for his findings of dolphin toxicity; there’s only one reason for me to talk to him. I think what’s happening is the government is mad at him for coming out with these findings. The government stands to really get hurt quite badly because they’ve been allowing this toxic meat to be sold. He’s saying that we took his comments out of context. But we released the full transcript. He said what he said when he said it. In fact, the original transcripts are a lot more damning than were actually used in the movie. There’s a sequence where we said, “Do the fishermen know that; do the dolphin hunters know that the meat’s this toxic?” And he said, “Oh yeah, they know very well my work.” Then I said, “Well, why do they continue to do it?” And he said, “For the money.”

What emotional effect do you think The Cove has on viewers?

People stop going to dolphin shows—they’re not going to take their kids to them. Jacques Cousteau said the educational benefit of watching a dolphin in captivity would be like learning about humanity by watching a prisoner in solitary confinement. To really experience dolphins, you’ve got to see them in the wild. When you see a dolphin show, you’re just witnessing a human display of dominance.

Has The Cove had any impact on attendance at dolphin shows in Florida and other places?

I know that Sea World just fired 350 people and they mentioned that it was partly due to the [bad publicity from a] trainer being killed by a Sea World orca. I testified with [HSI’s] Naomi Rose in Congress, and I think that we got the biggest fine that the government ever levied against the captive dolphin industry. To get any social change to happen, you need to influence the politics. But to influence the politics, you have to have the grassroots support. The Humane Society and my little organization, the Oceanic Preservation Society—we’re working together.

The Cove has won probably more awards than any documentary in history. But the most exciting award I had was the Genesis Award. We were fresh off the Oscars, but to be in a room with [more than 800] like-minded people eating vegan food and celebrating each other in that way, with so much love and compassion for this cause—the respect for other creatures—it was so heartwarming, so wonderful. It was just a beautiful, beautiful event—the one that I look at as being more valuable to me than winning an Oscar in terms of how much more emotionally it meant to me.

Are you expecting the hunt to continue in 2011?

The mayor of Taiji has said that the movie has already shut down the demand for dolphin meat by $6 or $7 million a year. I think it’s going to be extremely hard for them to make a business of killing dolphins after this movie gets seen widely in Japan.

Right now you’re working on a film about extinction.

We’re causing the biggest destruction since the extinction of the dinosaurs, through habitat destruction, pollution, overconsumption of animals, and invasive species. We’ve become this human asteroid. My goal is not just to create awareness that this is going on, but to actually try to move the needle in causing significant change. The working title of it is called The Singing Planet. And that’s because everything from the insects to blue whales has been singing; we just haven’t been listening. That’s sort of the common emotional way to get into the story, when you realize that we’re extinguishing the voice of these animals that have song. Some of the songs that you hear are so complex and so beautiful and haunting and ethereal. I think when people start to hear these voices, it will awaken compassion.

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe