In 1988, after a decade that saw record sales of animal fur, a representative from the Humane Society of the United States met in Europe with other advocates to plan an end to an industry built on cruelty. Only a year before, the first ladies of the U.S. and what was then the USSR had famously appeared together in Washington, D.C., wearing full-length mink and sable coats.

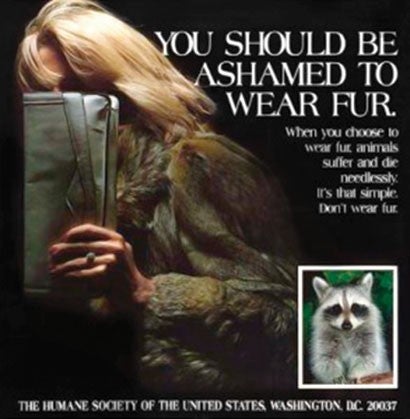

Undeterred, advocates at the meeting agreed on a trans-Atlantic plan to end the use of animal fur in fashion. Dutch activists had already shrunk the public’s demand for fur in their country. With permission, the HSUS borrowed a Dutch image and slogan for a nationwide campaign in the U.S. The ad showed a woman in a fur coat, her purse raised to cover her face, next to the words “You Should be Ashamed to Wear Fur.”

But the goal of ending the use of animal fur in fashion remained out of reach in the 1990s and 2000s. Even as full-length animal fur coats lost their appeal, trim made from animal fur, often misidentified on labels as “faux,” became popular. As less fur sold in the United States and Western Europe, markets in Russia and China buoyed demand. As people questioned whether it was right to kill animals for their fur, the fur industry fought back hard with public relations campaigns. As China’s economy exploded, so did fur production there.

Now the HSUS and HSI are focused on enacting animal fur sales and production bans. In January, a California law went into effect that prohibits fur sales in the state, one of the world’s largest markets for animal fur (more than a fifth of the U.S. market). Advocates are campaigning to get a sales ban in New York state (another fifth of the American market) and have helped introduce bills in Massachusetts, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Washington state, Oregon, Rhode Island and Hawai'i. Fourteen municipalities have banned fur sales, including Ann Arbor, Michigan; Boulder, Colorado; Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Hallandale Beach, Florida. In June, Rep. Adriano Espaillat (D-N.Y.) introduced a bill to ban mink farming in the U.S. And the HSUS has asked Dillard’s, the last major U.S. retailer still selling fur, to stop. After our campaign generated 5,000 phone calls and 80,000 emails from advocates, Dillard’s took down the fur products on its website.

More than 80% of consumers surveyed consider animal welfare when buying apparel.

Vogue Business, 2021

The majority of designers are working with faux fur because they have understood the necessity to spare animals as much as possible; they understand it’s the right thing to do.

Arnaud Brunois, Ecopel

The next generation of innovators, I don’t think they’re interested [in animal fur]. Students today are seeking a whole other look. They’re looking to have fun—something that is very flamboyant. They like it when it is obviously unreal.

John Bartlett, Marist College

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe