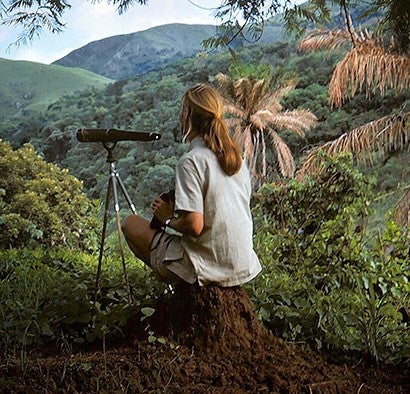

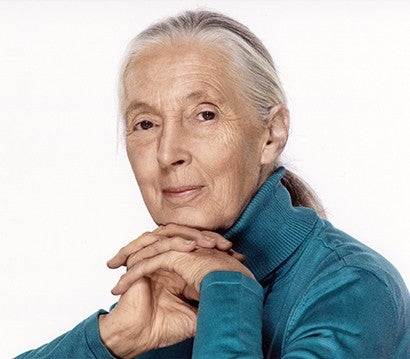

When a young Jane Goodall entered the forests of Tanzania to study wild chimpanzees, neither she nor those supporting her work imagined the influence she would have. Today, Goodall—Ph.D., DBE, founder of the Jane Goodall Institute, and United Nations Messenger of Peace—is recognized not only as a conservationist and animal activist, but as a source of hope that change is possible.

In this interview with Humane Society International president Jeffrey Flocken, Goodall discusses the power of storytelling, how humor helps spread her message and where she finds hope for the future.

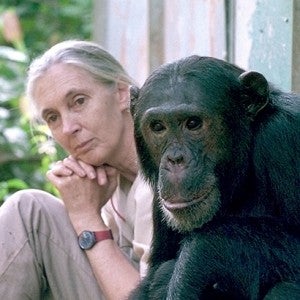

Before Dr. Goodall observed a chimpanzee using a bent twig to “fish” for termites in 1960, scientists believed that humans were the only species to make and use tools.

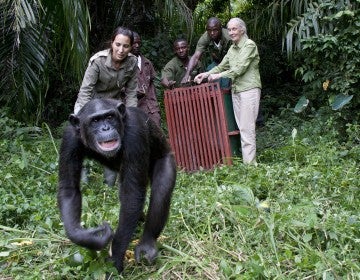

Dr. Goodall observed chimpanzees “adopting” orphaned youths and comforting each other after another chimp died, suggesting that they experience compassion.

Chimpanzees and humans share 98.6% of our genetic material, making them our closest relatives.

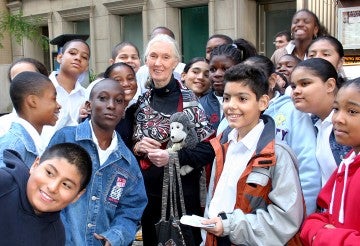

JF: You’ve worked with young people through the groundbreaking global Roots and Shoots program and other advocacy and education initiatives. You also were kind enough to spend an afternoon with my young daughter and our exchange student telling them about your life, and the need for them to create change in their own communities (which inspired my daughter to start a Roots and Shoots chapter at her elementary school). Why have you chosen to invest so much energy in young people?

JG: It has been my experience that most children have a natural love for animals unless they have been brought up to see them as mere things. Once young people understand the problem—understand that animals have personalities and emotions like us—and once they are empowered to take action, they start to create change. They influence their parents, grandparents, teachers, friends.

At a recent gathering of R&S in Tanzania, one 11-year-old boy said that now that he understood animals could feel pain, he would never hurt one as long as he lived. There are active R&S groups in almost 70 countries, and they are helping many different kinds of animals, refusing to eat meat from factory-farmed animals, volunteering in dog and cat shelters, making bird nesting boxes and insect “hotels,” peacefully protesting shark fin soup or the wearing of fur, and so on.

JF: Over time, your advocacy has broadened to include many animals—including those raised for food. Can you explain to the readers why it is important to think about how we treat all animals?

JG: It is important once you realize that every animal is an individual, with his or her own personality, mind and emotions. They all feel joy, frustration, depression, fear and, of course, pain.

At the start of a serious meeting, or during a talk, I ask the most important man to join me, and demonstrate to everyone how a female chimpanzee greets a dominant male while telling him what he must do—look big and intimidating while I approach submissively, take his hand so that he pats my head and then, emboldened, embrace him and make pant grunts in his neck. Sometimes I ask everyone present to stand and greet their neighbors in the same way. This reduces tensions in the most important meetings!

JF: You were 26 when you traveled to what is now Tanzania to study chimpanzees. What advice would you give to your younger self before embarking on that journey?

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe