The mountain lion known as P-47 survived fires, freeways and hostile ranchers. But in March, the 3-year-old big cat—tracked by California biologists since his kitten days—succumbed to a hidden hazard: an insidious form of food poisoning.

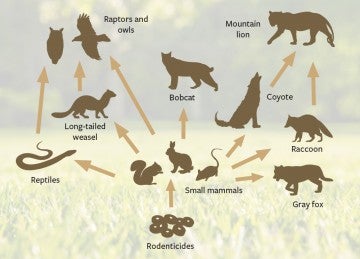

Six anticoagulant compounds—chemicals used to kill rodents—were found in P-47’s liver. He was also bleeding internally. He didn’t have to consume rat bait directly to become ill. As apex predators, mountain lions inadvertently absorb the toxins through their natural diets, eating poisoned rodents and other predators who feed on them. More than 90% of those tested in the Santa Monica Mountains region have been exposed to rodenticides, as have most bobcats and coyotes.

“The number of animals who get either compromised or die from these poisons is enormous,” says John Griffin, director of urban wildlife programs for the HSUS. “We’re awash in rodenticides.”

Anticoagulants prevent blood clotting and can lead to hemorrhaging. Wildlife specialists know the signs well. When veterinarian Antonia Gardner at the HSUS-affiliated South Florida Wildlife Center treated a lethargic juvenile barn owl with no visible injury, “he started oozing from the places where we were giving fluids,” she recalls, noting that the owl was likely fed poisoned rodents by his parents. “And he was developing bruising because his capillaries were not clotting.”

Even animals not killed directly suffer; researchers have linked the compounds to weakened immunity, recently confirming connections to mange in bobcats. Globally, anticoagulants show up in many animals, from Algerian hedgehogs to European fish. Another type of rodenticide, a neurotoxin, is devastating San Francisco’s wild parrots. One study even placed rodenticides above climate change in the list of threats to California’s endangered San Joaquin kit fox. “These poisons have made their way completely throughout the food web,” says Lisa Owens Viani of Raptors Are the Solution, an advocacy group working to end rodenticide use. “We feel like it’s our modern-day DDT because it’s so widespread.”

Now lobbying for restrictions across California, Owens started RATS after neighbors discovered dead Cooper’s hawks, including a fledgling found in a pool of blood. Raptor families consume hundreds to thousands of rodents annually, but “we are poisoning the very solution to the problem,” says Viani. Ventura County officials recently confirmed the value of natural predation, finding that raptor perches placed near levees resulted in fewer ground squirrel burrows than in areas treated with rodenticides.

A humane backyard is a natural habitat offering wildlife plenty of food, water and cover, plus a safe place to live free from pesticides, chemicals, free-roaming pets, inhumane practices and other threats. And it's so easy to build!

The Environmental Protection Agency banned over-the-counter sales of the most acutely lethal, single-dose anticoagulant rodenticides in 2015, yet pest control operators still use them. Off-the-shelf anticoagulants, which kill rodents through multiple feedings, also wreak havoc. Rodents don’t die instantly, instead becoming easy prey: Researchers in Colorado observed hawks preferentially preying on prairie dogs made lethargic by rodenticides, and a photographer watched a hawk picking off rats exiting a bait box. Cats and dogs die after breaking into boxes or eating poisoned prey.

The desire for out-of-sight, out-of-mind solutions causes immense pain for millions of rats. People use rodenticides routinely, says Griffin, but “there should be a higher threshold for justifying that kind of control.” Prevention is key: Seal holes, secure food and garbage and remove bird feeders. “Is it really worth feeding the birds,” asks Viani, “if you’re going to have a rat problem and then you’re going to put out poison, which in turn is going to kill other birds like hawks and owls?”

While homeowners work on permanent prevention, live traps can help transport rodents outside. Some cities are experimenting with fertility control bait—a promising development in the search for humane solutions, says Griffin: “This kind of approach is the future.”

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe