My husband and I were contemplating whether to hike the 3-mile trail in Utah’s Zion National Park that September day. I’d read that this trail was our best chance to spot bighorn sheep, but after a week of exploring the five national parks in the state, our bodies were tired—and it was already late afternoon.

Our desire to see wildlife firsthand won, and after making it to the summit just in time for sunset, we descended the mountain and saw a group of hikers huddled together, passing around a pair of binoculars. Following their gazes, we spotted a couple of sheep delicately perched on the steep cliffs. We joined the impromptu gathering and watched the animals in wonderment. Someone let us borrow the binoculars and, despite being hundreds of feet from the animals, we got a close-up glimpse of their lives.

While traveling, I’ve also witnessed starkly different wildlife encounters. At Assateague Island National Seashore in Maryland, I saw a family approach the iconic wild horses. They stood within a few feet of the powerful animals, even as park rangers arrived to move the equines to a safer distance. In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I saw a large group of visitors and cars form around two elk. My husband and I stopped to admire the elk but quickly retreated to our car, feeling guilty for contributing to the crowding.

Approaching wild animals like this can seem harmless. After all, the animals are in their natural environment, and they may seem unfazed. But when we engage with wildlife inappropriately, we often inadvertently harm the animals we’re admiring.

A growing trend

The chance to see wild animals draws millions of people outdoors each year. A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service survey found that 86 million people participated in wildlife-watching activities in 2016 (the most recent year the survey was conducted), up from 71.8 million in 2011. Outdoor recreation has also been on the rise, with the COVID-19 pandemic encouraging even more people to get outside as indoor activities closed down.

Many recreation sites have been feeling the stress of increased visitation. Zion National Park had over 5 million visitors in 2021, around a 90% increase from 2010; July 2021 was the most visited month on record for Yellowstone National Park, with over 1 million visitors. To control crowds, some national parks have implemented seasonal reservation systems at their most popular sites.

With more people heading outdoors, and wild animals’ habitats shrinking, interactions are bound to occur. How we react when we spot wild animals can prevent conflicts, keeping both ourselves and animals safe.

Your presence exerts pressure on them. They’re responding to you whether you know it or not.

John Griffin, The HSUS

Subtle effects

People often impact wild animals in nature without even knowing it, says John Griffin, senior director of urban wildlife programs at the Humane Society of the United States. “Your presence exerts pressure on them. They’re responding to you whether you know it or not. They hear you, they smell you, they see you—often before you see them or hear them,” Griffin says.

A 2021 literature review found that small mammals and birds may change their behavior—including leaving an area or spending less time feeding—when people get within 300 feet of them (the length of a football field). For large mammals, human presence more than a half mile away can alter behavior. Further, a 2023 study assessed the impacts of human recreation on wildlife behavior in Glacier National Park. The researchers compared camera trap data from the summer of 2020, when the park was partially closed due to COVID-19 restrictions, to the summer of 2021, when the park experienced high visitation rates. They found that when hikers were present, 16 out of 22 mammal species altered their behavior by abandoning a habitat they previously used, using a habitat less frequently or shifting to more nocturnal activities.

The impacts of these behavioral changes aren’t immediately obvious. Visitors might see animals run from crowds, but they don’t see how repeatedly fleeing drains an animal’s energy and takes time away from essential behaviors such as foraging, resting, nursing and breeding. Human activities that induce animals to flee might also cause them to abandon their young, leaving them vulnerable to the elements and predators. Some animals become more nocturnal to avoid humans or abandon a highly visited area altogether.

Physiological changes, such as increases in stress hormones, are even less apparent to onlookers, says Courtney Larson, a Wyoming conservation scientist with The Nature Conservancy. Larson studies the impacts of recreation on wildlife. “Maybe an animal doesn’t run away or flee, but it has higher levels of stress when a person is nearby,” she says. “So you might think, ‘This animal is fine, I’m not impacting it because it’s not moving or changing its behavior.’” But having high stress levels repeatedly can negatively affect an animal’s health and their ability to survive and reproduce, Larson says.

Recreation can also alter the composition of wildlife communities. Some species—such as raptors, ground-nesting birds and larger predators—are more sensitive to human disturbances than others, Larson says. Those species might leave a habitat while others more tolerant of humans stay behind, disrupting the balance of that ecosystem.

Griffin notes that human activities can be especially disruptive when animals are mating, establishing a nest or raising their young. Bison mating season occurs from June to September, for example, corresponding with summer vacation travel. Older bulls will become increasingly aggressive during this time as they search for partners, which can result in conflicts with visitors.

The horse, now named Chip, became food-conditioned after getting fed by beachgoers who ignored National Park Service rules and regulations for years. He became increasingly aggressive toward visitors and was resistant to staff members’ attempts to move him out of dangerous situations. In May 2022, the National Park Service removed Chip from the island and brought him to our Texas sanctuary, Black Beauty Ranch, where he can return to more natural behaviors and live peacefully. He’s not the only horse to leave Assateague for the sanctuary: Fabio, who is now 30 years old, arrived in 2011 under similar circumstances.

Like wild horses, many other species that inspire awe are also imposing—and can be dangerous. Over three days in June 2022, two people were gored by bison in Yellowstone. The previous month, another visitor was gored by a bison and thrown 10 feet into the air after approaching the animal. In fact, bison cause more injuries to visitors at Yellowstone than any other animal. Even animals who appear nonthreatening can harm visitors: In Grand Canyon National Park, squirrels injure more visitors than any other animal.

Interactions don’t always end in injury, but they still put other visitors at risk. “If animals are fed, they typically want to be fed again,” says Biel. “It might not be the person that fed them that they become aggressive toward. It might be the person two hours after or two days after.”

Maybe an animal doesn’t run away or flee, but it has higher levels of stress when a person is nearby.

Courtney Larson, The Nature Conservancy

Cruel unintentions

Many people are drawn outdoors because they appreciate animals. But the excitement of a wildlife sighting can push us to engage in risky behaviors—which makes it easier for others to join the rule-breaking. Researchers studying human-bison conflicts in Yellowstone found that some visitors who were originally hesitant to approach bison decided it was safe after seeing others getting close.

It can be easy for a visitor to think they don’t have an impact as just one person, but our actions in nature don’t happen in a vacuum. “People don’t think about how their one time is really not just one time. The animals can learn from that, other people start to do it, too, so it all can add up to really negatively harm those wildlife species,” says Katie Abrams, an associate professor at Colorado State University who studies risk communication regarding human-wildlife interactions in national parks.

A single encounter can also set off a self-perpetuating cycle: When visitors encounter habituated or food-conditioned wild animals behaving in an unnatural manner, they might start perceiving these animals as pets or pests, says Abrams. At Assateague, wild horses can remind people of the domesticated horses they see on farms or during pony rides rather than wild animals. People may also feel like they are being “chosen” by a wild animal who approaches them, Abrams adds. That desire for a special moment can motivate people to escalate a wildlife encounter by feeding the animal, says Griffin.

Yet because human disturbances don’t leave a “physical scar on the landscape,” says Larson, many outdoor recreationists likely underestimate their impact on wild animals.

Larson has seen positive changes, though. When she started studying the impacts of human recreation on wild animals 10 years ago, she got a lot of confused responses from people wondering how they could be harming animals by walking in the woods. Today there’s a growing understanding of both the costs and benefits of outdoor recreation, which she says may be due in part to the rise in outdoor activities during the pandemic—and the overcrowding that came with it.

The ultimate goal is less about changing wildlife behavior than it is about changing human behavior.

Mark Biel, Glacier National Park

Changing the way we recreate

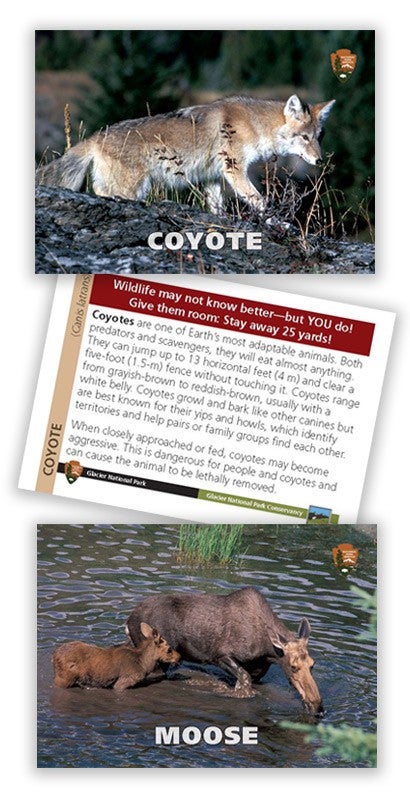

To help grow awareness and encourage behavior changes, park personnel and nonprofits such as the HSUS are educating people about the risks of close interactions and providing resources to prevent conflicts. Our Wild Neighbors program provides information on species people may encounter in nature, such as their natural behaviors and ways to prevent and resolve conflicts.

The HSUS also recently partnered with local organizations and government agencies to launch a rental program for bear-resistant storage canisters along the Rogue River National Recreation Trail in Oregon. This area draws tens of thousands of visitors each year and experiences human-bear conflicts, often caused by people improperly storing attractants such as food, garbage and scented toiletries.

Human behavioral changes, like the ones the bear canister program hopes to drive, are crucial in curtailing harmful human-wildlife interactions. “If you don’t remove the attractant, you’re going to continue to have the problem,” says Susan Getty, an HSUS wildlife protection public policy specialist.

Solutions to human-wildlife conflicts should use a multipronged approach that addresses changing both wildlife and human behavior, experts say.

Glacier National Park has enlisted the help of a specially trained border collie for that very purpose. In 2016, the park launched a wildlife shepherding program with Gracie, Biel’s own dog, to move habituated bighorn sheep and mountain goats away from high-visitation areas. (For safety, Gracie stays on a leash and does not physically interact with the animals.)

Preliminary indications show the program is working, but Biel says the park needs more data to compare Gracie to other hazing methods. What is clear is that having Gracie by his side helps Biel communicate with the public. “If it’s just me walking around, people might ask me where the bathroom is or what time the next shuttle comes,” he says. “But when they see Gracie, it opens up that door to get that educational message out.” With Gracie in tow, Biel talks to upward of 100 visitors a day about wildlife safety.

How to reduce your impact on wild animals

Research species you might encounter so you know what to expect.

Research species you might encounter so you know what to expect.

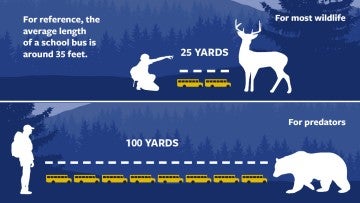

Look up and follow park regulations on distances to keep from wildlife—they can vary between parks.

Look up and follow park regulations on distances to keep from wildlife—they can vary between parks.

Know what gear you need to keep yourself and wildlife safe (e.g., bear spray, bear canisters, etc.).

Know what gear you need to keep yourself and wildlife safe (e.g., bear spray, bear canisters, etc.).

When walking your dog on trails where they’re allowed, keep them leashed so they don’t disturb wild animals—and always pick up after your pup.

When walking your dog on trails where they’re allowed, keep them leashed so they don’t disturb wild animals—and always pick up after your pup.

Do not leave any food or garbage behind for wild animals to find (yes, even food scraps such as apple cores and banana peels).

Do not leave any food or garbage behind for wild animals to find (yes, even food scraps such as apple cores and banana peels).

When in doubt, err on the side of caution and give animals more space.

When in doubt, err on the side of caution and give animals more space.

Ask a park ranger if you have questions.

Ask a park ranger if you have questions.

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe